https://www.musical-u.com/?p=40983&preview=1&_ppp=f4ffc936a3&utm_source=ping_070517&utm_medium=ping&utm_campaign=ping

Are you ready to find out how modern neuroscience and psychology can make you a better, more satisfied musician? Check out Musical U’s interview with The Learning Coach – Gregg Goodhart.

http://musl.ink/learn2learn2

Effective Practice: Lessons from Neuroscience and Psychology, with Gregg Goodhart

Innovative music educator Gregg Goodhart eschews the idea of “natural talent”; instead, he believes that passion and hard work are at the root of musical learning. Armed with this knowledge and a background in neuroscience and psychology, Gregg has developed a pragmatic teaching method that emphasizes acquiring talent by repetition and making good use of practice time.

Last time we talked with Gregg, he shared new paradigms for learning, competence, and talent. This time we asked him about how to actually acquire talent, the smart way to practice, the neuroscience behind repetition in learning music, and the secret to effective music learning.

Q: How can someone choose to be gifted? Do you feel that anyone can be successful musically?

This is a very complex answer. So, let me explain it like this: developing high-efficiency skill development or learning is like developing instrumental skills. It takes a lot of time, repetition, and mistakes, and you usually need to get coaching to do it well. A few figure out how this process works, and can coach themselves. However, even the “independent” learners may have someone walking them through this learning process; someone to teach them to teach themselves.

These students make radically better progress than their peers week-to-week. It is this very few we call “talented”. By putting these things to work early on, we can begin to develop and refine skill development the same way one develops instrumental skill, and we participate in “acquiring talent”. It’s pretty cool.

These students make radically better progress than their peers week-to-week. It is this very few we call “talented”. By putting these things to work early on, we can begin to develop and refine skill development the same way one develops instrumental skill, and we participate in “acquiring talent”. It’s pretty cool.

Beyond the basic ability to operate the instrument, there are many psychological factors that get in the way of learning, and you have to understand this to coach yourself, or a student, through it. If you’re curious about it, the free material on my website can give you plenty of information on the subject.

Q: Tell me about it! I experience those psychological factors first-hand, but often don’t know how to handle them. I know that one “way out” of that mess is deliberate practice. Can you please more about what “deliberate practice” is, and what its benefits are?

Since we are talking about music, let’s use the repetition process as an example. We know we need to repeat small bits of music to be able to play a piece fully.

Here is a diagram I use to explain how the repetition process should work:

This should occur for every repetition. How often your practice time looks like this is directly correlated with how good you will get. Now, how rarely do you think practice looks like this?

Probably about as rare as the occurrence of “talented” individuals.

For instance, what if every college music student entering a program had to take a course called “The Art and Science of Learning Music”, in which they are taught the skills of efficient practicing, and the repetitive, varied, reflective way learning works over time?

In the same vein, I do something called Practice Coaching by Skype for eight-week sessions. These are essentially one-on-one lessons on developing highly skilled practice habits, and they’re open to students of all levels. We address everything from how to start practicing more to how to train your brain to improve the way you practice. Here is a before-and-after from a pre-college student at the top music education college in America:

Here is a student before the eight weeks, not bad…

…And at her first prize-winning performance, eight weeks later!

Q: That’s amazing, Gregg. What sort of practice regimen do you feel is most effective for musicians?

Be curious about your practice, and your regimen will take care of itself.

This question has as complex an answer as, “How do I get good at the violin”, but here are a few quick tips:

If you want to practice 30 minutes more per day, don’t jump in whole hog with the full half hour. Start with 5-10 minutes and stop without guilt. Then, after two weeks, increase the time a little every week or two until you hit your desired practice time.

Making a little tweak, like recognizing we need to build a habit pattern for getting started, can be a game changer.

During that short practice time, be extremely focused on improving one or a few small things, over and over, constantly adjusting. Your teacher should be able to walk you through this. You will notice improvement in certain areas in the first week, and that will create more motivation.

There is far too much to answer here, but I have a free 34-page PDF with in-depth answers to developing practice regimens students and teachers. The section on “Habit Pattern Development” goes into some detail about building practice.

Q: So starting small, building up in increments, and continued repetition is a good approach. For those wondering about the science behind this method, what are the neurobiological changes that occur after many repetitions and much time spent practicing?

Everything we do or think is actually groups of neurons (brain cells) communicating with other neurons.

So, the first thing we have to do to learn a new skill is build a neural network. That is, we create connections between neurons.

During this process, the neo-cortex of the brain is lit up like a Christmas tree. We are in a state of confusion, trying to figure out where the network should be built. As we push through this initial confusion (an integral part of learning, not an indication of lack of ability), areas of the brain drop out of the action, and the skill becomes represented by a very small area. Researchers call this a process efficiency change. You have just built a connection in your brain that was not there before (i.e., you have learned the basics of a new skill!).

Q: How exactly does this “connection” get made?

Neurons communicate by sending electrochemical impulses (called action potentials) down a tube called an axon, across a gap called a synapse into another neuron. The axons in this newly formed network are uninsulated, and the action potential leaks out and travels slowly.

Attached to axons are cells called oligodendrocytes that produce an insulating substance called myelin. So, each time you do a repetition of, say, a short melody, if fires off an action potential that triggers the production of a little bit of myelin which insulates the axon so that the signal can stay strong and travel faster.

So is there anything you would like to be able to do stronger and faster on your instrument?

If you practice it even a little bit incorrectly, you are myelinating the wrong axons. Do you see why slowly and accurately works, and why the method many use – trying to play fast – does not work?

It takes a lot of wraps of myelin over a long period of time to get super fast and accurate. Therefore, working on something and getting it right once does not work. This process of myelination needs thousands of repetitions in the developmental stage. And no matter how talented they seem, students are in the developmental stage for years.

It takes a lot of wraps of myelin over a long period of time to get super fast and accurate. Therefore, working on something and getting it right once does not work. This process of myelination needs thousands of repetitions in the developmental stage. And no matter how talented they seem, students are in the developmental stage for years.

There is a lot more to this from cognitive psychology such as varied repetition and interleaving, as well.

Q: How can teachers use this information to help teach students how to learn?

Any good music teacher already knows much of what I’ve talked about here. What is new are the terms and concepts from cognitive and behavioral neuroscience and psychology, and how they fit together as part of a larger model. This information is powerful.

Any good music teacher already knows much of what I’ve talked about here. What is new are the terms and concepts from cognitive and behavioral neuroscience and psychology, and how they fit together as part of a larger model. This information is powerful.

My advice for teachers: be curious and learn how to read the research. Be suspicious and don’t accept any idea without investigating it. I wrote a blog post for teachers about this.

Understand, like you want your students to understand as they progress, that it will never occur as quickly as you would like and that it will take experimentation and some failure, returning to old “failed” ideas, and small victories. The good news: if it is done right, there will be a steady improvement along the way that is always satisfying.

Q: Terrific, Gregg. Tell us more about your workshops and presentations about improving the teaching/learning/practice of both teachers and students.

I’ve done everything from one-hour presentations to 10-day residencies at both the college and pre-college levels, including educating teachers of all academic subjects and coaches, based on my findings.

We do private practice consultations in which teachers can observe as we break down student practice methods, as well as refine and strengthen them. There may be days of workshops on how to use visualization to eliminate performance anxiety, large overview lectures for the community, and advice for professional development for academics.

I’ve developed a unique eight-week cycle of hourlong coaching sessions by Skype between lessons I call Practice Coaching. It is like rocket fuel for getting to a new level in one’s playing. More info can be found at Feel The Blearn.

Another thing I do is called a Practiclass – a masterclass for practicing. We take those few sections that never seem to be playable during performance and lessons, and fix them in 30 minutes or less. While we do this, I teach the audience the relevant neurological and psychological areas at work, and how they can use this knowledge in their teaching and practice.

Here is me doing one at Jacobs School of Music at Indiana University (this student is pretty advanced, but it works with all levels):

I also employed the Practiclass method while working with a pianist on Beethoven at the Houston High School for the Performing and Visual Arts:

Both of these followed a detailed lecture to the group of teachers and students present. The feedback for these classes has been overwhelmingly positive, with young students and professors alike praising the lectures.

Thanks so much, Gregg! Your clear-cut approach to practicing music is certainly very encouraging, placing musicians right in the driver’s seat regarding their musical progress. It’s clear that your research into how psychology and neuroscience concepts can be applied to music practice has really changed the way your students view learning.

Practice Smarter, Not Harder

With the way our brains are wired, it’s important that we recognize that there’s a right way and a wrong way to practice. Shortcuts may save you time in the moment, but will prove to impede your musical progress further down the road!

And remember: this thing we call “talent” is really just a cocktail of hard work, self-reflection, planning, and good practice habits. There is absolutely nothing stopping you from mastering that difficult piece of music if you’re willing to practice, the right way.

Are you ready to find out how modern neuroscience and psychology can make you a better, more satisfied musician? Visit Gregg’s website to check out his writing on music learning, learn more about his teaching methods, and find out about his upcoming talks and workshops.

The post Effective Practice: Lessons from Neuroscience and Psychology, with Gregg Goodhart appeared first on Musical U.

Good mentors provide perspective, offer their insights ba…

https://www.musical-u.com/learn/music-mentor/

Good mentors provide perspective, offer their insights based on past experience, and help their mentees advance to the next level of their training. So…how can you find a music mentor?

https://www.musical-u.com/learn/music-mentor/

A Minor Scale With A Bright Spot: The Dorian Mode

Scales are a powerful building block of understanding and making music. However, it’s not all just about major and minor.

Seven modes exist for your listening (and playing!) pleasure. They are found everywhere, from classical music and movie soundtracks to contemporary rock and folk music.

Let’s have a look at one of the most popular and versatile: the Dorian mode!

But first…

What’s A Mode?

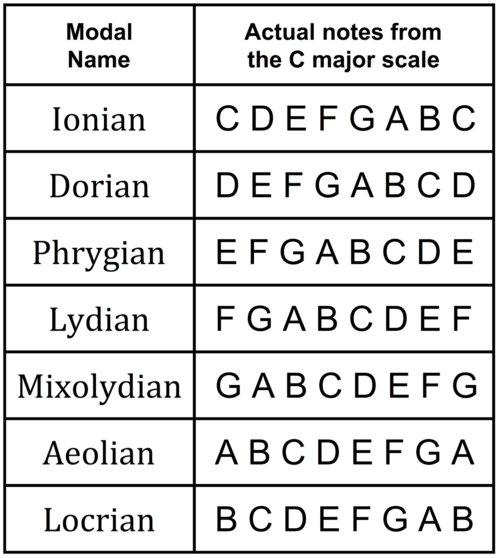

Modes are scales that are derived from the major scales. There are seven: Ionian, Dorian, Phrygian, Lydian, Mixolydian, Aeolian, and Locrian. Ionian in C major begins on C, and each subsequent scale starts on the next note of the C major scale as the one before it:

As you can see, each scale technically uses the same notes, but the tonic is shifted to a different note in each case!

Why Learn Modes?

Simply put, they will improve your playing, songwriting, and singing, regardless of what level you’re at as a musician.

Modes open up a world of music beyond just major and minor. Though modes can be divided into those two categories, each one has a distinct feel that is more complex than just being “happy” or “sad”. For example, while the classic Ionian scale’s upbeat and bright feel lends itself well to pop music, Lydian has more unusual intervals that makes it very suitable for jazz music. Hence, though the two modes are both major, they give music two completely different vibes.

You can probably see how this is valuable in songwriting; if you’re writing a sad song, you have multiple avenues you can explore within the realm of “sad”. You could go with the wistful, melancholy Aeolian, or experiment with the more gloomy, unsettling Locrian mode.

The Dorian Mode

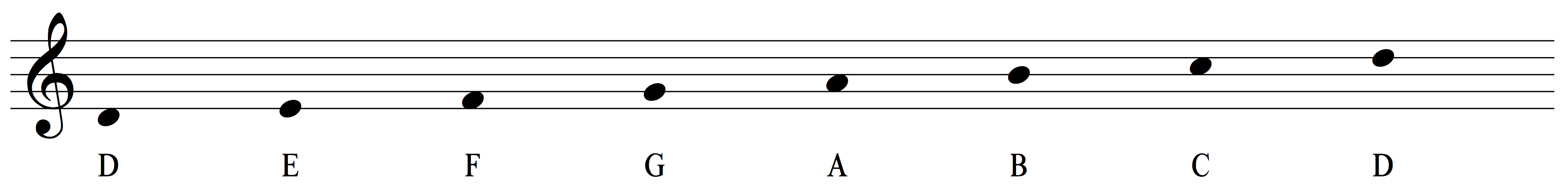

As we learned above, a mode is derived by changing which note in the scale is used as the root note. Dorian is simply the mode that has D as its tonic in C major, and is therefore played D-E-F-G-A-B-C-D:

Like each mode, Dorian has a specific tone-semitone pattern that remains as the backbone of the scale, regardless of the key it’s played in. The pattern in Dorian is tone-semitone-tone-tone-tone-semitone-tone. The intervals that result from this pattern lend Dorian its minor quality.

Transposing Dorian Mode

Dorian mode does not have to start on D; you can make the root note any note, transposing the mode into whatever key you fancy.

There are two ways to transpose Dorian:

- Use the tone-semitone pattern previously mentioned to figure out the notes the scale should have, starting on any root note you want.

- Derive Dorian from a major scale. Dorian mode in any key will have the same accidentals as the major scale a whole tone below it!

For example, B Dorian will have the same key signature (three sharps in this case) as A major.

Comparing Dorian to Other Scales and Modes

Dorian is a minor mode that differs from some of its modal cousins by only one note! Let’s see how it relates to two others that it has close ties to.

Dorian and the Natural Minor Scale

Dorian is similar to the Aeolian mode (natural minor), with the only difference being the major sixth found in the Dorian mode. This raised sixth degree lends a “bright spot” to the Dorian mode; this is often exploited in music.

Dorian and the Major Scale

Though Dorian is derived from the major scale (Ionian mode!) and uses the same notes in a given key, they have completely different moods. This occurs because the tonal center in Dorian is different than in Ionian, resulting in a different tone-semitone pattern, different intervals, and a different mood!

When and How Is Dorian Used?

Dorian is very versatile and can work with both major and minor keys. Traditionally, Dorian was commonly used in traditional Irish and other folk music.

Today, it is primarily found in jazz and blues, because its raised sixth degree gives a drive and brightness to the mode that works well with those styles. Elements of Dorian mode are also seen in pop, rock, and metal.

The Dorian mode works beautifully when layered with the pentatonic scale, and the two are frequently used together for a powerful effect.

You’ve almost certainly heard this mode in action before. Some well-known tunes that use it are:

- “Wicked Game” – Chris Isaak

- “Oye Como Va” – Santana

- “Purple Haze” – Jimi Hendrix

- “Eleanor Rigby” – The Beatles

- “Impressions” – John Coltrane

Practicing Dorian Mode

As with anything, it’s a good idea to start with the absolute basics – this is a little different from your typical major or minor scale, and really getting the feel of the mode may take a bit of time. Here’s a good step-by-step way to get comfortable with Dorian:

- Begin by practicing the scale itself, ascending and descending, getting comfortable with the tone-semitone pattern.

- Then, proceed to intervals and scale interval patterns. Pay attention to whether each interval is major or minor, and what mood it gives when played by itself.

- Experiment with building chords and triads built on the notes of Dorian mode. Use the raised sixth degree to add interest to the music!

- Try improvising in Dorian mode using a backing track! Play around with intervals, scale patterns, and major and minor chords.

Dorian Mode and Different Instruments

Dorian is used slightly differently depending on which instrument it’s being played on. For example, guitarists commonly use it as a stand-in for the minor pentatonic scale, as its raised sixth gives it a nice “bright spot”.

Dorian mode is commonly used by the bass guitar as part of the rhythm section.

On the piano, Dorian is more popular still; in fact, it is the most common minor scale found in jazz piano. It can be used alone, or overlapped with other scales.

It doesn’t stop there; this mode can also be found in violin, flute, saxophone, and other melodic instruments, especially those commonly used in jazz music.

Digging into Dorian

In today’s music, the Dorian mode is one of the most popular and useful seven-note scales. Its versatility lends it to a variety of music styles, and its characteristic raised sixth gives it an interesting major-minor ambiguity.

Try to listen for Dorian in popular music; you’re sure to find it in a variety of genres! As you hear more and more examples of it in use, your ear will get more and more reliable at recognising it straight off.

Use the tips in this article to start familiarizing yourself with Dorian, and check out our Ultimate Guide to the Dorian Mode for even more theory, playing exercises, and instrumental applications of this versatile mode!

Check out a trip down memory lane with Claire and The Pot…

https://www.musical-u.com/learn/from-solo-musician-to-a-band-that-works-or-how-marc-became-a-potato/

Check out a trip down memory lane with Claire and The Potatoes!

Composing music in a classical style can put restrictions…

https://www.musical-u.com/learn/compose-creatively-breaking-rules/

Composing music in a classical style can put restrictions on your creativity, especially if you are looking to create your own sound. Thankfully, in the age of technology, there are many ways to create new sounds – and even new instruments! https://www.musical-u.com/learn/compose-creatively-breaking-rules/

Paul Harris is one of the leading voices in music educati…

https://www.musical-u.com/learn/the-practice-process-your-map-to-musical-success/

Paul Harris is one of the leading voices in music education in the UK and his forward-thinking publications have influenced music teachers around the world. Learn more about his book

“The Practice Process”.

https://www.musical-u.com/learn/the-practice-process-your-map-to-musical-success/

I forget where I first heard the saying: “You can’t learn…

https://www.musical-u.com/learn/you-cant-learn-to-swim-in-a-barrel-full-of-water/

I forget where I first heard the saying: “You can’t learn to swim in a barrel full of water”

What do I mean by that?

Well, just as you are only fooling yourself if you splash about in a barrel of water and call it “swimming”, so too are you fooling yourself if you manage to divorce your musical training from… music!

https://www.musical-u.com/learn/you-cant-learn-to-swim-in-a-barrel-full-of-water/

Whether you’re just beginning your musical journey or you…

https://www.musical-u.com/learn/5-steps-setting-reaching-music-goals/

Whether you’re just beginning your musical journey or you’ve been a musician all your life, we all have dreams about where we see our musical skills down the road. No matter what your dream entails, we have great news for you: you can get there! All you need to do is map out your strategy.

https://www.musical-u.com/learn/5-steps-setting-reaching-music-goals/

What is the Kodály Method?

There are almost as many approaches to learning music as there are musicians. Every teaching style has a philosophy behind it, and this philosophy influences what is taught and how it is taught. The interactive, collaborative, and highly kinesthetic Kodály method of learning music was developed by Hungarian composer and educator Zoltán Kodály in the early 20th century. It combines several powerful techniques for developing the core skills of musicianship.

Because it focuses on the expressive and creative skills of musicianship (rather than the theory or instrument skills) the Kodály approach is very closely related to the world of musical ear training.

In fact, it could arguably be seen as an approach to ear training, since it is primarily your musical ear which Kodály develops.

We’ll learn more about what Kodály can do for you, but let’s first look into the man behind the method.

The Life of Zoltan Kodály

Born in Kecskemét, Hungary in 1882, Zoltan Kodály showed musical aptitude from an early age, composing for his school orchestra in his childhood.

After completing a Ph.D. with a thesis entitled “The Strophic Structure of Hungarian Folk-Songs”, Kodály began traveling extensively, accumulating music knowledge through his trips to the Hungarian countryside and his stint in Paris, where he studied with French composer Charles Widor and discovered the music of Claude Debussy. By this point, he was becoming a prolific composer, collaborating with Béla Bartók with whom he created a collection of Hungarian folk songs.

Upon his return to Budapest, he became a professor of music theory and composition at Liszt Academy. His big musical break came in 1923, when he was commissioned to compose a piece to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the union of the two cities Buda and Pest. The resulting piece, “Psalmus Hungaricus”, catapulted him to national-treasure status, as well as giving him international recognition.

He went on to write two operas, “Háry János” and “The Spinning Room”, which also became internationally popular. His body of work was a distinctive blend of classical, late romantic, impressionistic, and modernist – rooted in the folk traditions of Hungarian music.

Kodály continued to teach at the Liszt Academy for the majority of his remaining life, and after retiring as a professor, returned to the academy as a director in 1945.

Philosophy of the Kodály Method

Growing up with political disquiet in his country, Kodály sought out a way to preserve Hungarian culture, and found the answer in music.

Having been exposed to many styles of music education, Kodály found problems with the existing methods, especially taking issue with the fact that music education started so late in most schools. One story goes that in 1925, Kodály, overhearing schoolchildren singing, was so appalled that he set out to overhaul Hungary’s music education system.

He began writing articles and essays to raise awareness of the low quality of Hungary’s music education system. He believed the solution was better-trained teachers, an improved curriculum, and more class time devoted to music in general.

Not without drawing the ire of fellow music educators, Kodály dedicated himself to the project of music education reform, creating a new curriculum and new teaching methods.

Kodály was a firm believer in the importance of heritage and culture in one’s music education; he asserted that there was no better music than that of a child’s culture to teach children basic musical literacy. To this end, the system he developed integrated the singing of folk songs in the pupils’ mother tongue.

Finally, in 1945, Kodály’s work was applied in the ways he hoped it would; the new Hungarian government started to implement his ideas in public schools. This was soon followed by the opening of Hungary’s first music primary school.

This school was so successful that over a hundred more schools like it opened in Hungary in the following decade.

It didn’t stop there; the ideas of these music schools were presented at a conference of the International Society for Music Educators (I.S.M.E.), held in Vienna. Another conference held in 1964 in Budapest allowed other music educators to see Kodály’s work first-hand, leading to a steep increase in interest and to the widespread adoption of Kodály’s principles by his fellow educators.

The Creation of the Kodály Method

The Kodály method as we know it today was not technically developed directly by Zoltan Kodály himself. Rather, it was a system that evolved organically in music schools in Hungary under Kodály’s instruction and guidance.

Kodály’s friends, colleagues, and students helped develop this method by picking out techniques found to be the most interactive and engaging to create a method that focused on the expressive and creative skills of musicianship (rather than the theory or instrument skills). Many of these techniques were adapted from existing methods, altered to fit the context of Hungary. The resulting method relied quite heavily on exercises and games, and integrated the Hungarian cultural aspects.

With its folk foundation and its creative integration of movable “do” solfege, sounded-out rhythms, hand signals, and collaborative exercises, the Kodály method can be adapted to suit children’s music education worldwide, and nicely complements more traditional and orthodox approaches to music education. And more and more adults are discovering the great benefits of Kodály.

The Central Principles of Kodály

- Music should be taught from a young age. Kodály believed that music was among, if not the most important subject to teach in schools.

- Music should be taught in a logical and sequential manner.

- There should be a pleasure in learning music; learning should not be torturous.

- The voice is the most accessible, universal instrument.

- The musical material is taught in the context of the mother-tongue folk song.

Kodály for Children

The original method that Kodály pioneered was created with children’s development in mind. With the method, young children unconsciously learn the basic musical elements: solfa, rhythm, hand signs, memory development, singing, and more. Because the music education is already rooted in the culture they are immersed in, learning can occur both in the classroom and at home, with family. Early Kodály music education for children has countless benefits.

The original method that Kodály pioneered was created with children’s development in mind. With the method, young children unconsciously learn the basic musical elements: solfa, rhythm, hand signs, memory development, singing, and more. Because the music education is already rooted in the culture they are immersed in, learning can occur both in the classroom and at home, with family. Early Kodály music education for children has countless benefits.

…and for Adults!

The Kodály method is not just for children! Since training starts with simple steps and segues into more complex exercises as a knowledge base is created, adult musicians on every level will also find the method useful. The concepts of rhythm, relative pitch, and improvisation taught in the system are universal.

Similarities and differences with the Orff Approach

You may be acquainted with Orff Schulwerk, another music education approach developed by composer Carl Orff in the mid-20th century. Some characteristics of Kodály may remind you of the Orff Approach, but the two methods are distinct.

Similar Philosophies…

Both Kodály and Orff believed that discovering the innate pleasure and beauty of music should be a central tenet of musical education, and that music education should be social, and ideally, rooted in students’ heritage and culture.

As a result, both approaches use an element of “play” in their pedagogy. Additionally, the two philosophies can be said to have a shared motto: “Experience first, intellectualize second”, meaning that students unconsciously absorb musical knowledge through the interactive exercises. Only then are they asked to put pen to paper and articulate the principles behind the music.

…Different Strategies

Where the Kodály method uses existing music as its basis, Orff is largely improvisational. Kodály is vocally-oriented with goals of sight-reading and sight-singing, whereas Orff uses body instrumentation and simple percussive instruments with an emphasis on rhythmic development and improvisation.

Where the Kodály method uses existing music as its basis, Orff is largely improvisational. Kodály is vocally-oriented with goals of sight-reading and sight-singing, whereas Orff uses body instrumentation and simple percussive instruments with an emphasis on rhythmic development and improvisation.

It can be said that Kodály is more grounded in theory and geared towards ear training than Orff; this is seen in the way that it teaches musical notation from the beginning, whereas Orff delays this until students make sufficient progress.

Generally speaking, the Kodály method is more structured and sequential, whereas the Orff Approach is less systematic and more free-form. Each have their advantages, but the Kodály method is arguably more useful in honing a musician’s inner ear. This further comparison discusses their shared ideology while contrasting the teaching styles of each one.

How Kodály compares to traditional music education

Obvious differences include the one-on-one teacher-student relationship in traditional music lessons versus the group activities of the Kodály method.

While individual attention is valuable in music education, group learning allows for more avenues in creativity and collaboration.

Regarding lesson content itself, traditional music education focuses on teaching a specific skill set for a specific instrument, whereas the Kodály method starts with one’s own voice as the original instrument, and slowly expands its teachings to apply to any instrument.

What Principles Does Kodály Involve?

This method places an emphasis on intuitive, interactive learning. To that end, the techniques used engage the student as much as possible, integrating body movement, singing, and group exercises.

1. Movable “Do” Solfa

Solfa (aka solfège) is a system for relative pitch ear training (i.e. recognising and following the pitch of notes) which assigns a spoken syllable to each note in the scale.

Musicians who haven’t studied solfa often think of it as “the do-re-mi system”, and while this hints at its nature, it actually vastly understates its power and versatility.

The key advantage is that by learning the musical role and distinctive sound of each note in the scale, it becomes easy to identify (and sing) notes simply by recognising where they fit in the musical context.

By using solfège to teach the pitch side of musical listening and performance skills, the Kodály approach ensures that musicians have a natural and instinctive understanding of the notes they hear.

2. Hand Signs for Movable “Do” Solfa

The Kodály Method includes the use of hand signals during singing exercises to provide a visual aid for the solfa syllables. The height that the hand rests at while making each sign is related to the pitch, with “do” at waist level and “la” at eye level. The spatial distance between the hand signs of different pitches corresponds to the size of the interval.

This even further reinforces the power of the solfa system in ear training; the student associates each pitch not only with a memorable syllable, but also with a specific hand motion made at a specific level. The hand signs complement and strengthen solfa learning.

If you want to try it out yourself, the Mobile Musical School has a useful exercise for practicing singing with hand signs!

3. Rhythm

Rhythm is often a neglected area of ear training. Many students simply don’t know how to effectively develop their rhythm skills, or how to connect them to the rest of their music learning.

The Kodály approach provides a clear systematic way to think about and speak rhythms in music which very much complements the solfège system for pitch. Kodály exercises encourage the participants to aurally, visually, and physically engage with the rhythms they’re playing.

Note values are counted out loud with assigned syllables that actually sound like the rhythms they spell out. For example:

Kodály students learn to speak and sing rhythmic patterns using specific syllables, and so develop a framework for understanding rhythm by ear and performing it accurately.

4. Creativity

Although we often think about frameworks as limiting sets of rules, in fact they can provide a structure which gives you confidence to experiment.

This is the case with the solfège and rhythm systems in Kodály teaching: by having clear systematic ways to understand pitch and rhythm, the musician is empowered to be creative and confident in music.

An example would be improvising sung melodies, or changing the rhythm of a song in creative ways. These tasks can seem intimidating to a musician who has been taught in the classical tradition, but with the Kodály approach, musical tasks like these are simple and enjoyable.

5. Collaboration

At its heart, the Kodály approach is a very human and social one, involving plenty of musical collaboration. From the earliest lessons, students are encouraged to perform together and play or sing duets, rounds, and other musical forms which allow both collaboration and creative improvisation.

Examples would be students singing together and taking turns to improvise different melodies while the other sings an accompaniment, or playing clapping games where their rhythms interact and synchronise in fun ways.

How Can I Start Learning Kodály?

Though originally designed with young children in mind, the principles of Kodály are universal. Musical U has many free solfa resources. You’ll also enjoy these free Kodály-style rhythm and syncopation exercises.

There is a worldwide network of organizations that are promoting the Kodály method today. For more information about Kodály music learning and to find a class near you, visit:

• The Organization of American Kodály Educators

• The British Kodály Academy

• The International Kodály Society

The Kodály method is for everyone; musicians of all levels and walks of life can find something in this spirited and hands-on approach to learning music.

You can even become your own Kodály teacher! Check out these book recommendations for learning Kodály, and integrate Kodály techniques into your musical training. Most of all, Zoltan Kodály believed that music learning should be enjoyable, so look for ways to collaborate, and make sure to find ways to be creative with every step of your music learning.

The post What is the Kodály Method? appeared first on Musical U.