With a seemingly infinite number of scales available to the modern musician, it can be a little difficult to know where to start!

The major scale may get touted as the most important, but in fact, there is another scale that is even more versatile, pleasant-sounding, and (once you get the hang of it) easy to play.

Introducing…

The Pentatonic Scale

By definition, any scale containing five pitches per octave can be said to be a pentatonic scale. However, for the purposes of this article, we will focus mainly on the major pentatonic scale, whose notes consist of the five most common pitches found in folk melodies and children’s songs.

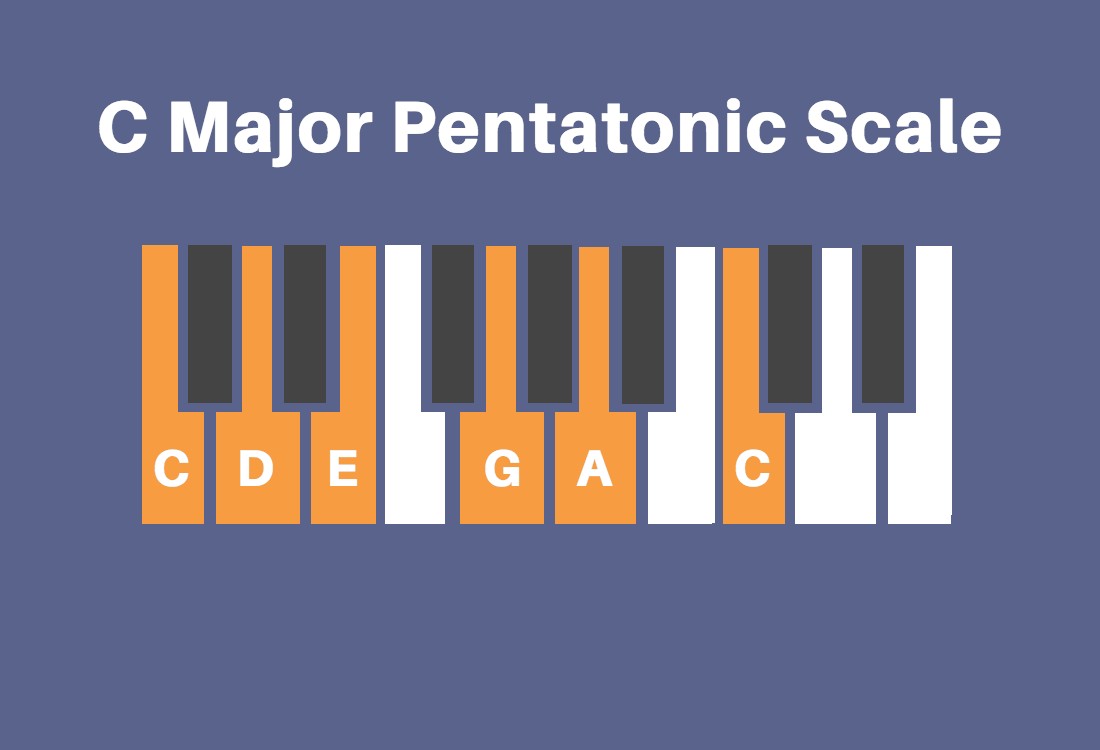

The major pentatonic scale uses scale degrees 1, 2, 3, 5, and 6. Take a look at the C major pentatonic:

The notes used in the C major pentatonic scale are C, D, E, G, and A.

The scale degrees used remain the same for all pentatonic major scales.

How Does the Pentatonic Compare to the Major Scale?

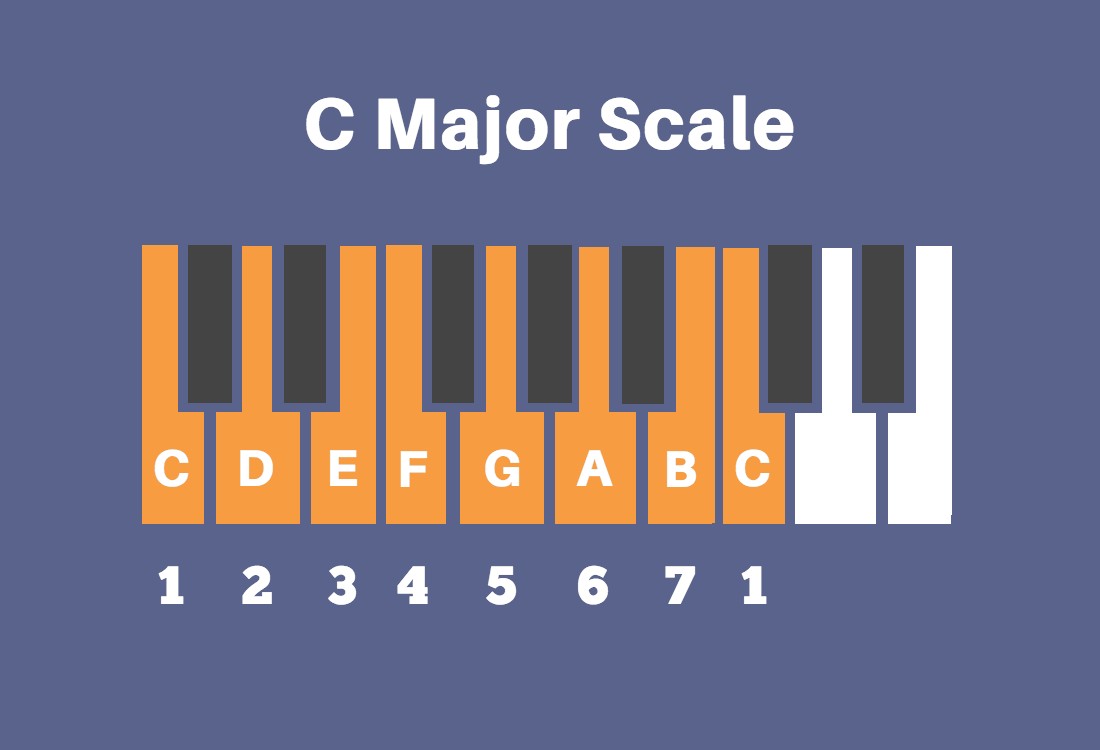

The major scale, often the first that musicians learn, is built on seven degrees:

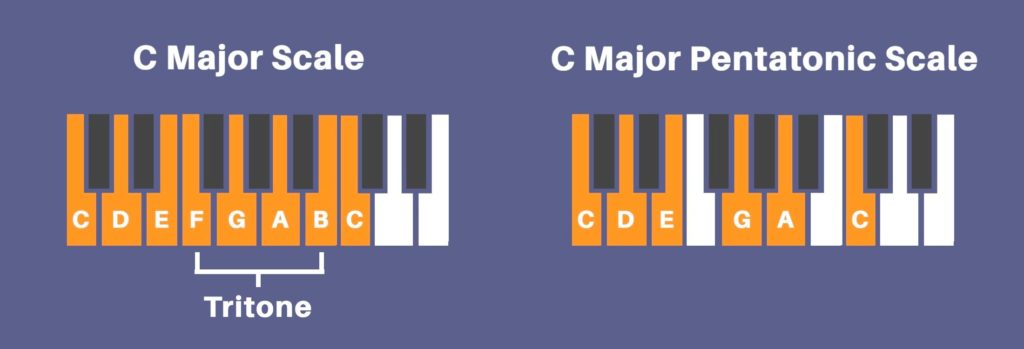

To derive the major pentatonic scale from the major scale, simply remove degrees 4 and 7.

The removal of these in the major pentatonic scale contributes to its consonant (or pleasant) sound. In the major scale, the fourth and seventh degrees form what is called a tritone, which is a fairly sinister-sounding interval (so sinister, in fact, that it was given the nickname of the “Devil’s Interval”!). This interval lends tension and suspense to the major scale.

The removal of these degrees in the pentatonic scale leaves only consonant intervals: a major second, major third, perfect fifth, and major sixth.

Where is the Pentatonic Scale Used?

Well, an easier-to-answer question would be “where isn’t it?”.

The scale has been around for a very long time. Nobody knows exactly how long, but instruments believed to be as old as 50,000 years old have been found tuned to the pentatonic scale.

The major pentatonic scale is ubiquitous in musical cultures all around the world, America, Europe, Africa, India, China, and Japan, to name a few. In fact, the Japanese anthem is based on the major pentatonic scale!

Being a major part of traditional and folk music, the major pentatonic scale carried over into the styles that sprouted from these genres: gospel, bluegrass, and jazz. As these styles further evolved into blues and rock, guess what remained?

That’s right: the major pentatonic scale.

Today, it’s a hallmark of jazz, blues, and rock music, as it offers an excellent improvisational framework for these styles.

Why Learn the Pentatonic Scale?

Blues guitarists aside, this is a must-learn scale for any musician. Here’s why:

1) It’s versatile!

The major pentatonic scale can be used to solo over almost anything. It sounds great over major chord progressions, minor chord progressions, and the 12-bar blues. It even works beautifully with major church modes: that is, the Ionian, Lydian, and Mixolydian modes.

2) It’s easy!

Once you memorize the simple patterns of the pentatonic scale on the keyboard and fretboard, your fingers will be able to play it by memory.

3) It’s already in the music you want to play!

This scale’s ubiquity in popular music means it’s well-worth learning for any musician wanting to cover a famous tune.

Playing the Pentatonic Scale on the Piano

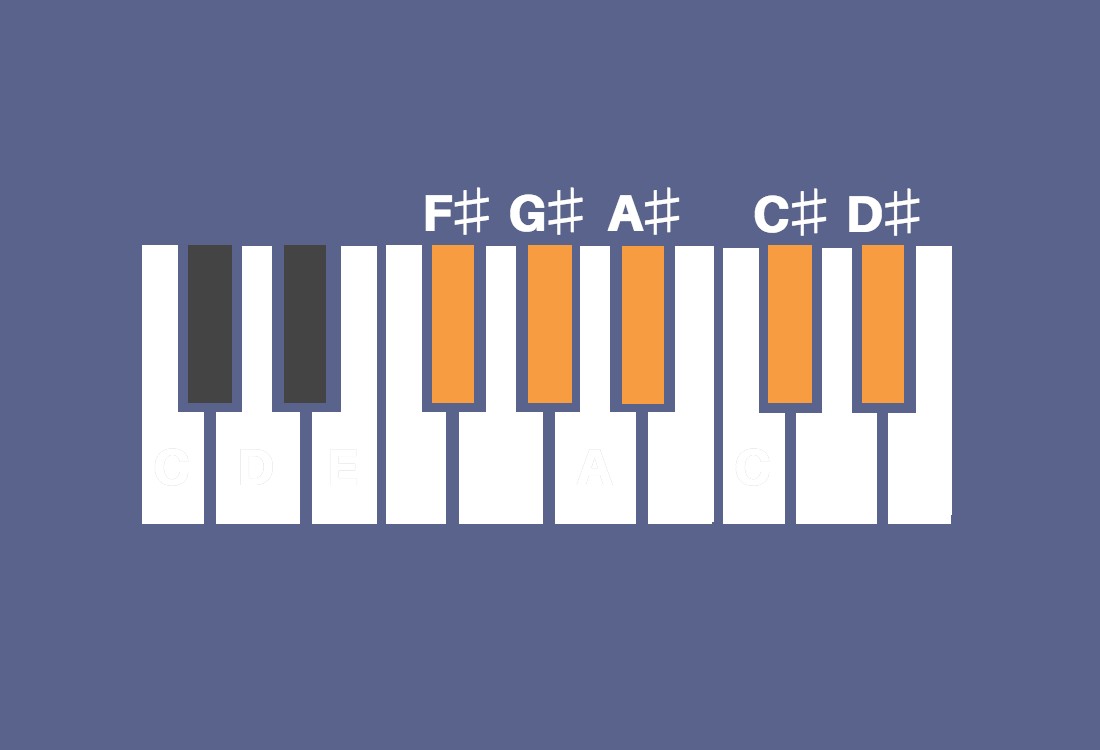

Try this simple exercise: starting on F♯, play an ascending scale using only the black keys on the piano.

What do you hear?

We’re guessing you would describe the feel of this note pattern as “Asian” or “Oriental”. You have in fact just played an F♯ major pentatonic scale!

To transpose this scale into another key on the piano, simply pick out scale degrees 1, 2, 3, 5, and 6, and play them in ascending order. If you know your key signatures, it’s smooth sailing from there!

Playing the Pentatonic Scale on the Guitar

There are numerous ways of playing the major pentatonic scale, with a single key having several corresponding patterns.

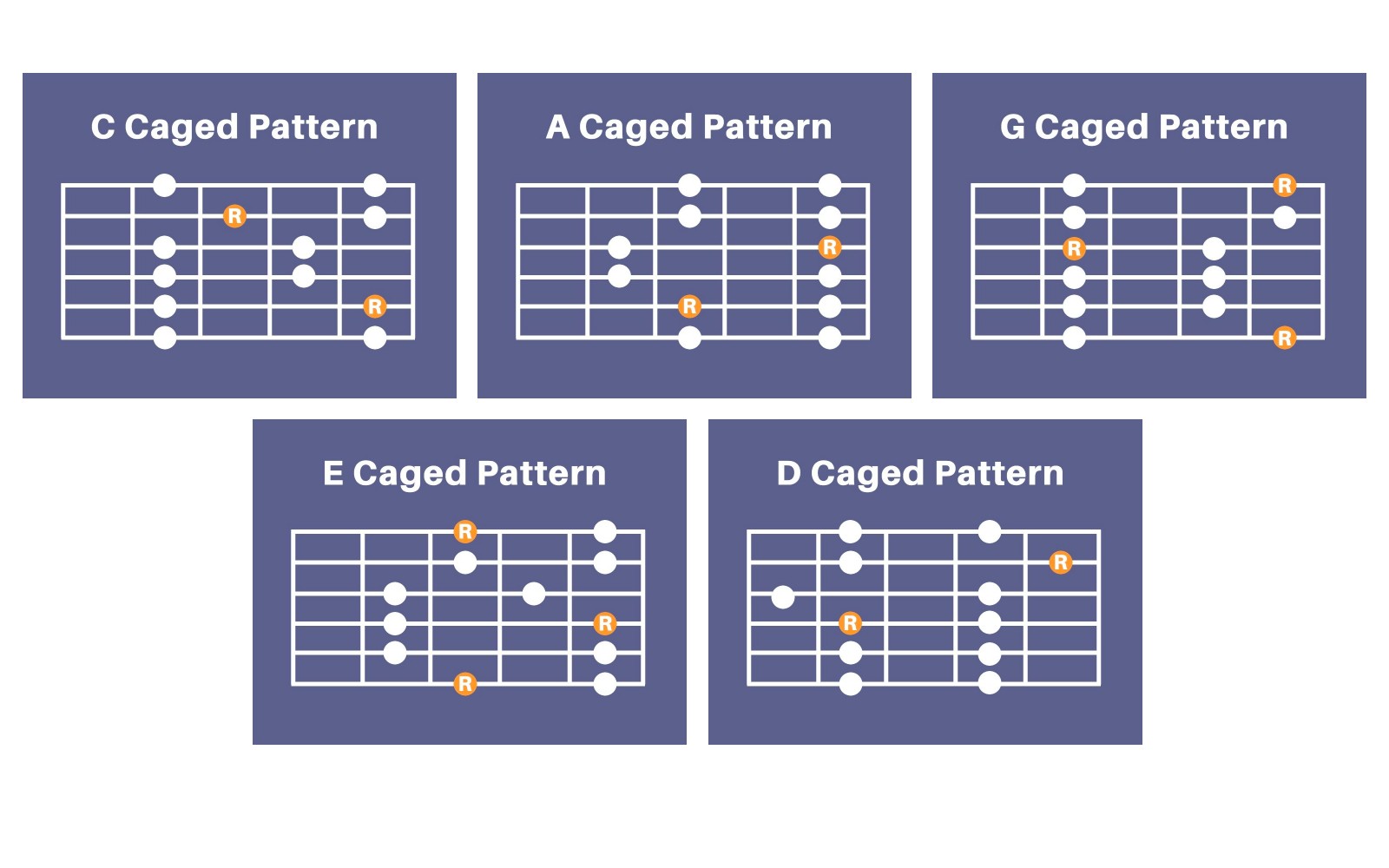

To really master the major pentatonic on the guitar, make use of the CAGED system.

Sounds a bit scary, right?

Fear not! The CAGED system simply gives you five patterns on the fretboard that you can use to play the major pentatonic scale. Each pattern is based on the corresponding open chord shape:

Once you memorize these patterns, all you need to do to transpose the scale into any major key is move up and down the fretboard! The starting position may change, but the fingering pattern won’t.

Beyond the Major Pentatonic

Remember when we said that any scale with five pitches per octave can technically be considered a pentatonic scale?

This means that the major pentatonic scale is far from being the only pentatonic scale!

The Minor Pentatonic

This scale is a great one to learn as a follow-up to the major pentatonic, and can easily be derived.

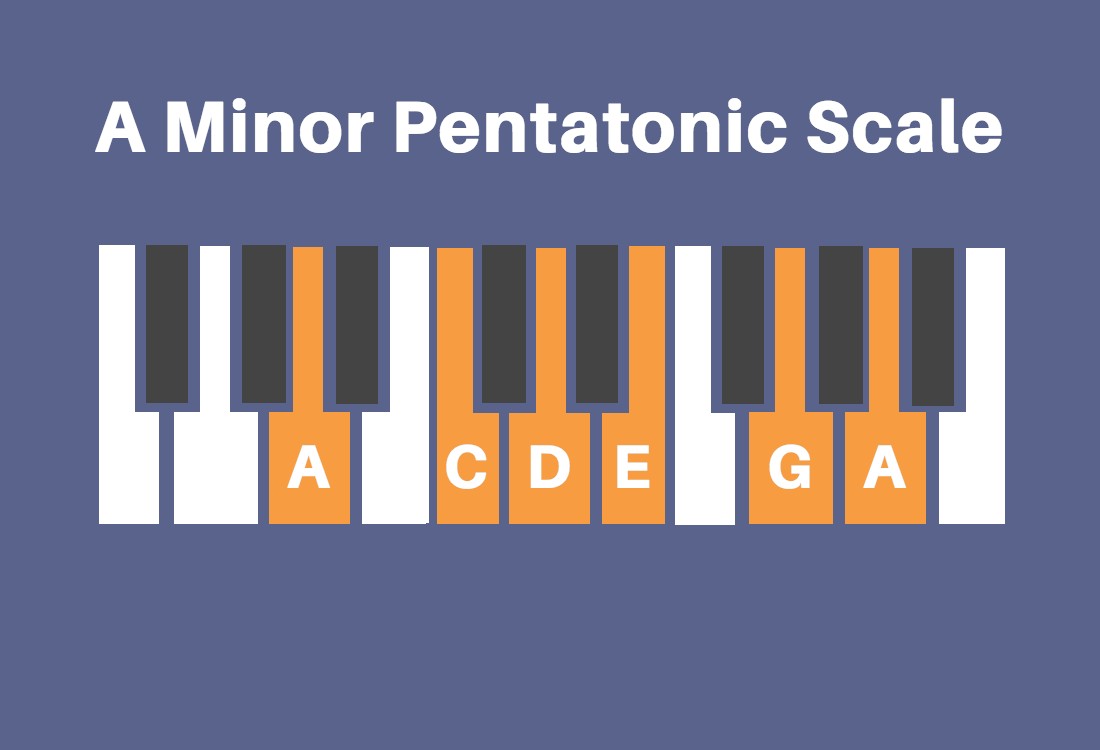

The relative minor pentatonic scale will contain all the same notes as its major cousin, but will start on a different note. The last note of the major pentatonic will be the tonic of the relative minor pentatonic scale.

For example, seeing as the C major pentatonic ends on A, the relative minor pentatonic scale will be A minor:

Other Pentatonic Permutations

If the only true requirement of a pentatonic scale is the presence of five pitches per octave, there are thousands of possibilities! Try building your own unique pentatonic scale by raising, lowering, and shifting pitches. With so many possible combinations, you’re bound to find something that sticks in your head.

Get Playing!

Now that you’ve seen the versatility of pentatonic scales, it’s time to add them to your repertoire!

Start small: take a second, pick up your instrument, and try out the C major pentatonic.